Auschwitz-- ,,Arbeit Macht Frei" (Work makes you free)

It's easy percieve history as a recitation of events, strung together like dull little pearls on a single thread, one after another after another. You start at one end, and like counting a rosary you let centuries slip through your fingers, and in the end all you've got is the other end, and nothing left of the middle. History can be a frightening subject, if you look inside each of those little pearls, if you scrub off the film to reveal the clarity underneath--and see your own reflection. Those who do not learn history, it is said, are doomed to repeat it. This assumes, of course, that we understand history. Aside from an inherent bias--written by the winner--it can be interpreted on a bias or the basis of incomplete information; perhaps not intentionally but nevertheless skewed. Or insufficient. We think we understand, we link solitary events into a cohesive whole as if building with legos, matching color and shape and discounting or disregarding those pieces that don't fit.

And sometimes, most of the pieces just don't fit.

History is indeed little more than the register of the crimes, follies and misfortunes of mankind.

Edward Gibbon (1737 - 1794)

Studying German history has been enlightening to me, both for presenting me with a past with which I am unfamiliar, but also for presenting the basis of the modernity I am coming to know and love. I have no relationship to this past, except secondhand, though my distance to my own country's history is only slightly less. Yet I know many people who have experienced this past directly or indirectly. Considering Germany today, it is almost inconceviable to contemplate its horrendous and murderous past, to concieve that this past would have yielded this present. Many scholars have devoted their careers to "explaining" Nazi Germany, its causes, methods, and eventual defeat overshadowed by industrial-scale genocide. The point of historiography is to highlight that there is no "one" explanation. Some consider Nazi Germany to be a "phenomenon", an unlucky coincidence of unique factors (Mommsen) resulting through a procession of "cumulative radicalization"; others attribute the NS regime to Hitler's growing madness and that of his cronies; still others point to the economic situation in Germany during the Weimar period as the crucial factor that allwed nationalism and racism (as were appearing throughout Europe, not just in Germany) to take the murderous form it did.

Looking at propaganda of the era, it is difficult to evaluate: the phrases seem trite, brash, common, and often outright racist; how could these have appealed to anyone? Couldn't they see what was coming? Of course, we have the benefit of hindsight, and a "collective radicalization" theory would indicate marginally increasing pressure (antisemitism, etc.). If you place a frog in boiling water, it will jump out. But if you place a frog in cold water, and slowly heat it, it will be boiled: so can we concieve of the increasing restrictions on Jews, or the increasing hardship.

As Hitler and the NSDAP went about getting elected in 1933, they didn't start out with billboards calling for Jewish extermination. They campaigned with propaganda aimed specifically at different portions of the population, targeted and sometimes contradictory, but blatantly populist and popular. Economic protectionism and racial nativism abounded.

(This poster is from the 1930's, and encourages Germans to buy domestic rather than imported goods. The top translates as "Germans buy German goods." The bottom text translates: "German Week/German Goods/German Labor.")

The parallels are striking. The propoganda pandered blatantly; it promised, extolling the virtue of home-produced goods (Freedom fries, anyone? Agricultural tarrifs? Made in USA?) over imports in a slanted tilt towards autarky. Hitler promised, and delivered, jobs to a Germany beset by mass unemployment and inflation comparable to that of Zimbabwe today. He built the Authbahn, and bought out the middle class with automobiles and refrigerators; with modernity comes complacency. The Hitler Youth provided in many areas the only opportunity for leisure activities or vacations for many young people. Patriotism was encouraged, "German values" above all, with an implicit--and sickening--sense of racial superiority gradiating into blatant antisemitism.

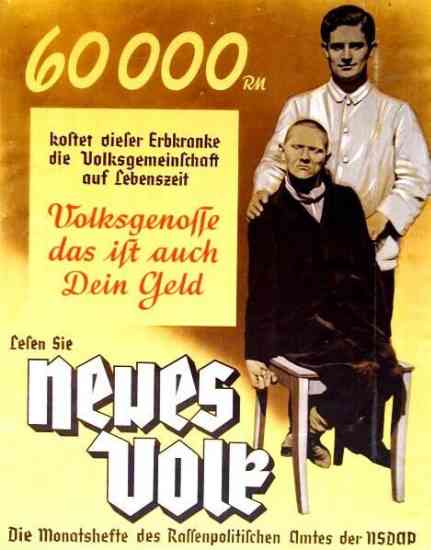

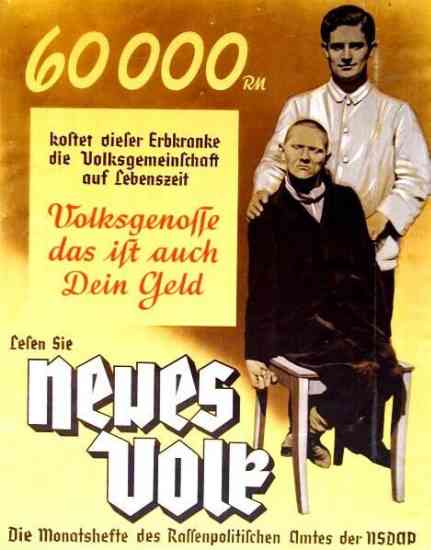

(This poster is from the 1930's, and promotes the Nazi monthly Neues Volk (New People}, the organ of the party's racial office. The text reads: "This genetically ill person will cost our people's community 60,000 marks over his lifetime. Citizens, that is your money. Read Neues Volk, the monthly of the racial policy office of the NSDAP.")

(Nazi anti-Semitic poster. The caption: "The Jew: The inciter of war, the prolonger of war." This poaster was released in late 1943 or early 1944. Courtesy of Dr. Robert D. Brooks.)

Antisemitism was worse in Russia, Poland, and France than it was in Germany; yet in Germany it found voice and eventual resonance, culminating in the Reichskristallnacht where SS, SA and others smashed Jewish shops, murdered over 100, and caused mayhem. It seems paltry in comparison to the millions later to be exterminated, but it markes a significant escalation of violence.

Hitler was democratically elected; even the rapidly disintegrating and defunct institutions of the Weimar Republic broadly constituted democracy, probably more so than is seen today in Russia or most of Africa and Central Asia. He came to power via the ballot box and despite Hindenburg, but consolidated political power through the use of poltiical violence (Bessel); unevenly and piecemeal. The eventual accretion of violent tendancies under the SS and the SA represented a consolidation of disparate forces. Bessel argues that political violence stems, to some extent, "simply" from a disenfranchised and disenchanted generation without economic prospects. Youth culture gone awry.

I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.

Albert Einstein (1879 - 1955)

Many of the members of the resistance "movement" (perhaps totaling no more than 500,000) were initially supporters of the NSDAP in 1933 who only later moved to oppose him. Much of the opposition was centered around Communist or Socialist groups, outlawed perforce and persecuted. Opposition to specific Nazi policies was common, but restricted itself to specific issues and was usually a disagreement over the means, not the end; widespread disagreement with the "ends" didn't exist, or at least not until it was too late. Either through propoganda, or coercion, or fear, citizens were induced to denounce their neighbors.

Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe.

H. G. Wells (1866 - 1946), Outline of History (1920)

It's hard to concieve of the "final solution" as anything but utter madness on a sociopathical scale; to think that so many millions of lives were lost for a deluded dream is simply incomprehensible. Some scholars argue that Hitler wasn't personally involved with much of it, that overzealous subordinates took it upon themselves to acieve Hitler's ends. Famously, Himmler became sick and threw up when viewing a concentration camp; even he couldn't stomache what they'd done. Scholars try to "normalize", to "historicize" this period, and treat it as any other period in Germany's history. While I understand their argument, and while I perhaps am too poorly read to exmaine that debate more deeply, I can't help but argue that genocide on this scale dwarfs both theory and history. At least if we can't understand it, we must never forget it.

There is no witness so dreadful, no accuser so terrible as the conscience that dwells in the heart of every man.

Polybius (205 BC - 118 BC)

_____PM.JPG)